Cherry Soda Pop, Strawberry Milkshakes, and Peggy Sue

“Mr. Sandman bring me a dream. Make him the [cruelest] that I’ve ever seen.” The 1950s was an era, that Hollywood loves to portray as being the age of innocence, where everyone whom wanted to could do so. Pulling back the veil, as is the case in mostly any society that has increase in class, some one or some group is usually being stepped on, being exploited, and being held back. It’s a difficult pattern to break out of, even mentally. Being a Mexican American, intellectually I know that I deserve as much as any anglo does in the form of prosperity. However, being that I was raised in the poor neighborhoods of La Mesa De Otay in Tijuana, Mexico, South-central Los Angeles, the farming and manufacturing town of Oxnard, and then east San Jose, my subconscious, every fiber of my being tells me that I don’t deserve it. Even if I work hard and smart for it, I still feel somehow like I’m less. With that said, the affects of racism persist still to this day. One could only imagine what the Mexican Americans must have gone through in times of even greater inequality; the 1950s were such a time. Mexican Americans for the most part did not share in the increased prosperity of that decade to the extent that their communities were broken up due to internal deterioration, encouragement, and physical destruction (as seen in lack of education, GI Bill, and eminent domain, respectively).

To illustrate the internal deterioration, “after 100 years of U.S. rule, New Mexicans lived in a ‘Third World’ environment.” Across the country it was the same story of deterioration. Education was the key factor in this process of decay. “The lower the median [level of year of education], the more segregated the schools were and the poorer the community” was. “In the Southwest, the median... was 5.2 compared with 11.3 for Euro-Americans and 7.8 for nonwhites.” In one of the poorest communities in Texas, the median was only a first to second grade education. Even Mexican Americans that served in the military, because that was their best option for lack of education, were stuck in a catch twenty-two situation as “they could not take advantage of the education stipends of the GI Bill because of a lack of education.” Another aspect of deterioration was the fact that the community simply lacked representation politically. Politics plays a major roll in the economic advancement of any group. So, when there is no political representation, neither is the encouragement of better wages for Mexican American workers or funding for schools in Mexican American communities. Even when politicians Chicanos do come to play a roll in politics, a huge sense of disillusionment occurs when not much is done. In 1957 El Paso, Raymond Telles was elected to mayor for two whole terms. However, “despite generating high hopes, Telle’s election brought little change. The 1960 census showed little improvement in living conditions for Mexican Americans; 70 percent of the Southside housing remained deteriorated or dilapidated. Sadly many organizations that helped Mexican Americans, vanished; mainly due to lack of funding, as was the fate of The American Council of Spanish-Speaking People. Aside from the inner deterioration of the Mexican-American Communities due to lack of education and economy, break-ups of the community were encouraged as well.

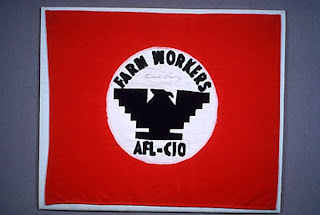

Encouragement of the Mexican American community can be seen in the union busting laws that were enacted to keep people from demanding better wages and work conditions. The Internal Security Act of 1950 and the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 were such laws. The McCarran-Walter Act is the most shocking as “it allowed the denaturalization of naturalized citizen. This was a tool used to get rid of union organizers” in order to break up unions. That’s like saying, “yes you’re part of the club. Well, you think too much. So, actually you’ve never been part of the club.” This was the case of Humberto Selix a man whom served in the military and later became union organizer but was later vilified for union organizing. Also durning that decade, the bracero program made it difficult for Mexican Americans to stay in communities with immigrant Mexicans. The bracero program caused a purposeful flood in a labor market in times of need, and then drained when it was convenient. “When labor shortages occurred, they opened the border’s doors, disregarding both international and moral law.” but during a recession from 1953-1955, the border “unilaterally closed [with] ‘Operation Wetback.’” When Korean Mexican American veterans came home to their designated communities, they found that Mexicans “still [living] in floorless shacks without plumbing, sewage connections, or electricity.” those thousands of Mexican American veterans added to “the [worsening] conditions of overcrowded housing and unpaved streets and sidewalks.” Mexican Americans not wanting to live in these conditions, However did have an opportunity to prosper elsewhere. The GI Bill encouraged a break up of the community as Mexican Americans whom could afford to do so, moved to the suburbs; which in turn further removed economy from the already poor inner city. The FHA’s Underwriting Manual more or less tells the banks to loan to mainly Euro-Americans because having other races “contributes to instability and a decline in values.” Another major positive change that occurred was that two new colleges in East Los Angeles made it accessible for working class Mexican Americans to get a college degree. Not only was encouragement a form of breaking up the Mexican American community in order to not spread the wealth, but also a physical break-up occurred in the 1950s

A physical break-up occurred in the 1950s. The physical manifestation of the above conditions were proven to be true when “federal loan policy allowed federal administrators and the housing industry to work hand in hand with developers, [to separate] the suburbs and inner cities.” highways physically segregated Mexican Americans from Euro Americans. The better situated Euro Americans moved to the suburbs and Mexicans moved to the dilapidated industrialized inner city. But the worst of it all was the actual bulldozing of entire communities. The 1949 Housing Act allowed for these atrocities to occur as expressways and freeways were built through them, land grabbing rights were given to the land developers to steal the land where Mexican Americans lived under powers of eminent domain. And although poor neighborhoods were considered expendable, Mexican Americans were not allowed to purchase homes in the suburbs. So, most moved to the older down-town areas. When eminent domain no longer became favorable practice, for land grabbing, it was, however, used to grab condemned properties, but was later handed over at 30% of the cost to land developers under the guise of the Federal Housing Act of 1949 which was expanded through the New Deal’s urban renewal program. The effect was severe; “By 1963, 609,000 people were uprooted nationwide, two-thirds of whom were minority group members. In Chicago alone, 50,000 city dwellers were uprooted from the Lincoln Park neighborhood in order to build five expressways.

To reiterate, Mexican Americans for the most part did not share in the increased prosperity of the 1950s. Their communities were broken up due to internal deterioration, encouragement, and even physical destruction. So, when you hear the sweet tunes of the 1950s, like “Put your Head on my Shoulder,” enjoy the music, but also remember to think of those who had other things to think about like finding a place to live. That era wasn’t only cherry soda pop, strawberry milkshakes, and Peggy Sue. That era was a time of great inequality. Not everyone could afford a home in the suburbs with a clock tower in the town square where kids would ride their Shwinn bikes and teenagers drove their sweetheart to the malt shop in their parents Buik. Okay, maybe I’m getting a little carried away with the cynicism, but It is true; not even in the thirty and forty year after that did my family have the stability of staying in a home for more than a few years. Even though my single mother wasn’t a migrant worker, she had to go where the work was. That meant living in places that she could afford; the poor parts of town. Even if my mom wanted us to live in a nice stable home and worked really hard (two full-time jobs), and made sure I went to school everyday no matter what (chicken pox), we simply couldn’t. We just had to survive. So, when I say that every fiber of my being tells me that I’m a lower class citizen that doesn’t deserve the same prosperity as Euro-Americans, I mean I simply am just used to it. Force of habit, maybe. Force of economy, maybe. Regardless of the situation, At the very least, I know intellectually that I do deserve it, and hopefully one day, before I die, I’ll come to fully realize it with all my heart... tear.

Comments