Bring on the Hate

Bring on the hate, because as we all know hate is a powerful word. Hate is also a great distractor. It distracts us from the fundamental problems that exist in our society, by blaming the easier target. The U.S. is widely criticized as being this type of country. On a radical and extreme side note, it can be a system that even creates criminals. However, this is not explored in this writing. So, as to explore only the subtleties, it is a system that can often create an subconscious sense of self-hate. How does that happen, one may ask? Well, consumerism is a major key to creating a burgeoning growth in a capitalistic society. Ads, such as the ones that bombard us with age defying beauty creams, as well as ads that once upon a time showed us only a homogenous Euro-American point of view, and that rarely showed us how ethnicity is beautiful, are examples of some forms of creating that sense of self loathing. Since we can purchase only those beauty cream but, cannot purchase the “nordic look”, we tend to feel like we are not as beautiful as the ads suggest us we should be. Furthermore, early on in consumer advertising, when “people of color” were advertised to, ads usually showed us a stereotypically glorified princess Pocahontas, this was just enough of a taste to let the “ethnic” kids know that they too could reach that status of being rich and famous. When reality hits, however, most economically disadvantaged people (like Mexican Americans) are not able to reach that status, we simply let the hate roll down hill. Sadly, Mexican Americans had their own targets (Mexican Immigrants). They tended to be darker than Mexican Americans which gave them a natural sense of superiority. To the point, Mexican Americans already in the United States reacted to the increase in immigration from Mexico mainly by seeing them as competition, by way of economics (Mexicans were taking their jobs) which in turn translated to a cultural identity crisis (questioning what it means to be Mexican American), and then a denial of the old Mexican culture (as can be seen in pejorative terms given by Mexican Americans to Mexican immigrants, Surrumatos).

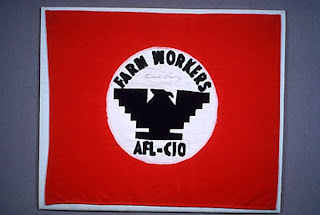

Mexican Americans saw the increase in immigration as economic competition. As David G. Gutierrez points out in his book Walls and Mirrors, “The massive immigration of the Mexicans in the 1920s resulted in increased tensions between Mexican Americans and the new arrivals... Mexican newcomers competed for space with Mexican Americans some of whose families lived in the United States for Generations.” Space, in the U.S. is usually defined as a the ability to rent or purchase, which means one needs to have a steady income, which of course means one needs to compete for jobs. “The Massive influx of Mexican Immigrants posed [a] challenge to working-class Mexican Americans in the form of increased competition in the labor market.” Because newly arriving Mexican immigrants were poor, their inability to live in the same neighborhoods as the rich or middle class Mexican & Mexican Americans, the communities became segregated. And because of that, a physical separation occurred, as well as a separation of class. This physical and economic division made it easy to pick on Mexican immigrants since most were poor and under educated. They were also viewed as “birds of passage,” meaning that they came to work temporarily with the full intention of going back home. The problem with this is that the “push-pull” economic factors still were the dictators of when Mexicans were allowed to come to the U.S. For example, “The Mexican population suffered a temporary setback in 1920-1921; as in the Southwest, many Mexicans [greasers, as they were called] were repatriated [some 150,000 from the whole U.S.] as a consequence of a deep economic recession.” However, “the situation improved as railroads and steel mills employed more Mexican workers. As agriculture recovered, the number of Mexican farmworkers swelled the population during the picking season.” Mexican immigrants being temporary residents, for the purpose of labor, was amplified by the mechanization of the large agribusiness that “displaced many year-round farmworkers.” in fact, between the years of 1920-1930 the pool of temporary workers “tripled, increasing from 121,176 to 368,013.” So instead of looking at the fundamental problems being caused for Mexican Americans by the ever expanding agribusiness (Mexican Americans were not needed as much for year-round work), it was easier to blame whom, and not what, was taking their jobs; To blame mexican immigrants, not machine of the agribusiness. Mexican American middle class and Mexican immigrant middle class were split as well, but this was mostly due to economic protection, rather than any physical economic divide via different neighborhoods. Mexican Americans began reaching, to find ways in which they were different from Mexican immigrants; this caused an identity crisis within the Mexican American community.

The identity crisis that Mexican Americans went through was a very serious one. Was one Mexican or was one American? By the rules of logic, they were neither. The rules of social science agreed with this case as well, since they were neither accepted by Euro-Americans which then conditioned them to not accept Mexican immigrants. To begin with the first case, “Euro-American racism played an important roll in [the adjustments between Mexicans and Mexican Americans] as well as defining the community,” since both groups were considered “greasers.” David Berkley had to use his father’s last name in order not to be segregated as a “greaser” in the military. After being killed in action, he was posthumously awarded the medal of honor. It wasn’t until years later that the origins of his Mexican ancestry were discovered. If it had been discovered before, it’s likely that he would not have been awarded the medal of honor at all, but wold have been considered just another casualty. Many business would not allow any “greaser” to patronize their stores; They were White only businesses. As it goes, Mexican Americans were not accepted in the mainstream of America, but at the same time were advertised to do so. The ambivalent messages of Euro-America caused further ambivalence within the Mexican American Communities as they began to attempt a love-hate relationship with Mexican immigrants.

Mexican Americans had no solid place with Euro-America which helped shape their view of Mexican Immigrants. Even though there was a large enough of an influx of Mexicans into the U.S. to create an actual sense of community for Mexicans and Mexican Americans alike, Mexican Americans, still did not want to accept the Mexican culture as being of value. The value that “on the positive side, the large presence of Mexican-born immigrants, reinforced Mexican culture and the Spanish language, affected the cultural identity of those born in the United States.” But because of the psychological trauma that Mexican Americans seemed to be facing due to the ambivalence of acceptance by Euro-Americans, Mexican Americans still tried to gain acceptance with Euro-Americans by joining them in the fight to “Americanize” their culture and completely ignore the richness of the Mexican culture. They denied their heritage by giving Mexican Immigrants derogatory names like “Surrumatos” (Southerner) in New Mexico; and “Manito” (little brother) in Arizona; “Chicano” (indigenous of Mexico derived from Mexica [pronounced, Meshica]) in California; and in the most extreme cases, “Wet-back” (due to the crossing of the border via the Rio Grande) originated in Texas, but incorrectly widely used throughout, since the majority of those crossing did it by land, and even arid desert. Even Mutual aid societies or Mutalistas that have been a tradition since the 1860s, began to split in to nativist factions only allowing Mexican Americans. The largest and oldest of exclusive clubs is the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), which on February 17, 1929 brought together all of the major exclusive clubs from across the country. It also broke from the Mexican consular leadership as “LULAC endorsed... its exclusion of noncitizens.” Their cause followed the times of the Civil rights movement in that it wanted to Americanize. Naively so, the Middle class Mexican Americans members of LULAC (whom were generally less educated than middle class Mexican Immigrants), copped out by saying that they were really against the “peon class.” The leader of LULAC Jude J.T. Canales’ view of “‘Mexicans from MEXICO are a PITIFUL LOT who come to this country in great caravans to retard the Mexican Americans’ work for unity that should be at the Anglo-Saxon level.” Making it easy to make this jump by Mexican Americans again was the superficial view of economics propelled by self-righteous religious organizations like Protestant ministries that opened community centers like Houchen. “Whether seated at a desk in a public school or on a sofa at a Protestant or Catholic neighborhood house, Mexican women received similar messages of emulation and assimilation.” these messages were promoted through community services like child care, health clinics, home economics classes, and Boy Scouting. These were places where Mexican American activists could be involved in “Americanizing” Mexicans. LULAC, did, however, help open the doors to “male” jobs for women. In the 1950s LULAC offered “carpentry classes - once the preserve of males - opened their doors to young women, although on a gender segregated basis.” On the individual level, for the most part, Mexican women viewed Mexican traditions as oppressive. As Rose Escheverria Mulligan points out, “‘I was beginning to think that the Baptist church was a little too Mexican. Too much restriction.’” Even though Mexican American women did not feel like they were “caught between two worlds, [as] they navigated across multiple terrains at home, at work, and at play. They engaged cultural coalescence. The Mexican American Generation selected, retained, borrowed, and created their own culture.” More so, they further denied their heritage in order to Americanize, as can be seen in the case study of From Out of the Shadows, where “seven of the seventeen [women interviewed for the book] married Euro-American men. Yet their economic status did not differ substantially from those who chose Mexican partners,” as was promised by all organizations like, LULAC, Houcheson, and the media.

To sum up, Mexican Americans already in the United States reacted to the increase in immigration from Mexico mainly by seeing them as competition, economically. And because of the identity crisis Mexican Americans faced, they denied the old Mexican culture, really causing a subconscious sense of self-hate. Mexican woman for example were pushed toward the idea that “life was a beauty contest.” with a 1932 ad for Camay Soap showing a “Hispano America” holding the product and making that statement. Thus telling Mexican American women that if they Americanized, they would could be superstars as well. Thus, causing a sense of disdain towards the old culture, finding any avenue to do so. The easy out? Mexican immigrants, especially those of lower economic and educational status, which was most. The hard and sad reality, however, was that their problems were much deeper, bringing us the negative byproducts that the fundamentals of competitive capitalistic society creates; That laws of supply and demand doesn’t just mean natural resources, it also means human resources. The system will take us only when it needs us.

Comments