Meh-sheeh-kah - Mexicano; Chicano

Chicano used to be a derogatory term that nativist Mexican Americans used to give to Immigrant Mexicans. In the 1960s, the term was taken back and used in honor of those most oppressed. This particular time in the U.S. was a time of great awakening and uproar; The Masses were speaking, as they say. The most recognized of the civil rights movement was that of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the fight for equality for African Americans. Although the Chicano movement was not initially recognized as being an actual fight for civil liberties by the African-American community, it eventually became a force to be reckoned with. The question is, was the movement successful? In my opinion, the Chicano movement was indeed successful in the 1960s and 1970s. Even if the results weren’t always favorable, the fact is, the Chicano community became conscious of the inequalities it endured, which then resulted in the formation of many Chicano rights advocacy groups that faced the problems with: the youth in education, labor, and socioeconomic/politics.

Education was a top priority for the Chicano movement, as it was the beginning of acceptance by the African-American community as being a legit issue for Chicanos. Even though the 1960 study of the census by economist Leo Grebler showed that “The median school grade in the Southwest for Spanish-surnamed persons more than 14 years of age was 8.1, versus 12.0 for Euro-Americans and 9.7 for other nonwhites, the median school grade attained by Spanish-surnamed in Texas was 4.8,” when the United Civil Rights Coalition formed in 1963, it “refused to admit Mexican Americans. Chicanos had to wait until the Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District decision (1970) for the courts to classify Mexican Americans as an ‘identifiable ethnic minority with a pattern of discrimination.’” Even so, throughout the 1960s, in El Paso’s historic Segundo Barrio, “poverty projects... brought youth together, who formed the Mexican American youth Association (MAYA), the most active Chicano organization.” 1967 was a big year for the Chicano movement as on January 17, the first bilingual education bill was introduced and was passed twelve months later. Also in 1967, in San Antonio, Tejano students formed MAYO at St. Mary’s College. Other chapters formed including high school chapters. “MAYO played a pivotal role in the bringing about civil rights for Mexican Americans and developed a master plan to take over boards of education.” Other student organizations that popped up during that time were the Mexican American Student Organization (MASO), the Mexican American Student Association (MASA). The most popularized of all the groups were the Brown Berets, which was founded by David Sanchez in 1968. The Brown Berets held demonstrations against police. That year massive walk-outs occurred with nearly 10,000 students from five schools across the city. These walk-outs spread to other parts of California and even occurred in Texas. The same year that the Berets were formed, The Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) gave Chicanos a tremendous boost as it helped them go to college with financial aid. “Before 1968 colleges could count the number Chicano students in the dozens.” Another famous organization to come about, MEChA (El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan: the Chicano Student Movement of Aztlan) established one of the most important outcomes of the Chicano movement in California and throughout the nation, Chicano Studies. Not only was education important in the awakening of the Chicano community and the Nation, but also labor played a key role.

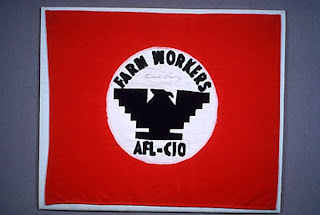

“On November 25, 1960 - the night after Thanksgiving - a one-hour television documentary, Harvest of Shame, was aired... [Narrator, Edward R. Murrow], began [with], ‘these are the forgotten people, the underprotected, the undereducated, the underclothed, the underfed.’ The documentary went on to tell the miserable plight of migrant workers, showing families working in blistering heat and living in rundown housing, enduring misery so that an affluent nation could be fed.” This documentary helped shape public opinion, but the Chicano movement was catapulted to the national level when on September 8, 1965 Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) voted to join the Filipinos’ Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) in a strike that would last five years against the grape growers of Delano in the San Joaquin Valley as well as the Cochella Valley in California (the biggest of which were the Di Giorgio Corporation and the Schenley Corporation). Eventually, “by the spring of 1971, Chavez and the Teamsters had signed an agreement that gave the [United Farm Workers Organizing Committee] UFCOW, [an affiliation that NFWA was forced to sign because of red-baiting], sole Jurisdiction.” “The Chavez movement in California... influenced the La Casita, Texas farmworkers resulting in the 1966-1967 strikes.” Although they were often violent strikes because of the Texas Rangers’ disruptions, and ended with very limited results, Chicano activism did increase. It spread to the midwest as Jesus Salas organized Obreros Unidos (United Workers) of Wisconsin in 1967. With the growing sense by all Americans of the need of Mexican laborers, Chicano activists, began to play an active roll in politics for the socioeconomic betterment of its people.

The 1960 census previously mentioned, “counted 3,464,999 Spanish-surnamed persons in the Southwest with a per capita income of $968, compared with $2,047 for white Americans and $1,044 for nonwhites. Of the Spanish-surnamed population, 29.7 percent lived in deteriorated housing versus 7.5 percent of Euro-Americans and 27.1 percent of other nonwhites... Unemployment, too, was higher among Chicanos than among whites.” Compounding with the statistics of the times, was the sense that “although Chicanos were not strictly segregated by the whites as were African Americans, most of them lived away from the white community, [and the fact that] social segregation still existed, and in places like Texas and eastern Oregon, ‘No Mexicans Allowed’ signs were common,” Chicanos decided to group together to enter into the world of politics by vote participation, and then by placing members into positions of power on a scale never seen before. Mexican Americans’ “Viva Kennedy” clubs “played an active role in [John Fitzgerald] Kennedy’s [JFK] narrow victory in 1960. without their vote, Kennedy would have lost Texas and the election... Officially, the U.S. Census counted nearly 4 million Mexican Americans: 87 percent lived in the Southwest, and 85 percent were born in the United States.” After Kennedy’s assassination the League of Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the G.I. Forum and “most Mexican Americans, [whom] were Catholic and Democrats, supported Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ..) who funneled patronage through [those] major Chicano organizations.” The Political Association of Spanish-speaking Organizations (PASO) was successful in getting elected a Mexican American slate of candidates into the Crystal City council. In 1964, a Mexican American congressional representative Eligio (Kika) de la Garza was elected. “As a consequence of the Civil Rights movement, [LBJ] was able to push through the Voting Rights Act of 1965.” Only a year later “in 1966, the Twenty-Fourth Amendment abolished the Poll Tax... Mexican Americans continued to increasingly run for office.” In 1965, in Mathis, Texas, Mexicans formed the Action Party that took control of the municipal government. Even though the federal government tried to help with its 1964 Office of Economic Opportunity Act (EOE), which created programs for the poor, such as a Headstart for Health, it had limited funds, and consequently became completely diminished with the election of Richard Nixon in 1968. In other politics, when LBJ signed the Chamizal Treaty (giving land back to Mexico) in 1967, it displaced 5,595 residents as they had to move back to the U.S. This caused an uproar during the committee hearings as protestors led by Ernesto Galarza, Corkey Gonzales, and Reies Lopez Tijerina, formed La Raza Unida (representatives of 50 Chicano organizations). Tijerina (El Tigre) known for the formation of La Alianza Federal de Mercedes (The Federal Alliance of Land Grants) “invoking the Treaty of Guadalupe [Hidalgo] in the struggle to hold on to common lands.” Gonzalez, first known for his boxing career, was better know for his activism in “the struggle for control of the urban barrios... In 1963 he organized Los Voluntarios (the volunteers), who protested against police brutality.” He then went on to direct Denver's’ War on Poverty Youth programs.” Gonzalez is also famous for his poem “I am Joaquin,” “the most influential piece of Chicano Movement literature.” He also formed the Crusade for Justice that held its first annual convention in 1969 in Denver, “where participants adopted El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan - A revolutionary plan that promulgated the therm Chicano as a symbol of resistance.”

As we can see the Chicano movement was indeed successful in the 1960s and 1970s as the conscious of the times awakened, which led to the formation of many Chicano rights advocacy groups that were involved with the youth in education, labor, and socioeconomic/politics. The Chicano movement took to the wind as it spread its wings and soared. Chavez, Tijerina, Gonzalez, and all of the people that followed these great leaders became proactive in a common cause. It was the cause that Chicanos shared in many common grounds with the cause of the African American civil rights. The masses spoke and they were heard. The echoes of that time can be heard still to this day when you walk down the street and hear us speak Spanish without the social stigma it once carried. The echoes of that time can be heard also when you turn on the radio and you hear the DJs talk about us and call us Chicanos.

Comments